The Brilliant Book Club is back, and we are finishing our discussion on Hilary Levey Friedman’s book, Playing to Win: Raising Children in a Competitive Culture. For more information on Brilliant Book Club, start here.

Before I continue, let me explain something about this book: it has many, many layers. Playing to Win is an extremely comprehensive, well-researched, insight-laden look at competitive activities for children in America. There is simply no way that any of us can include every aspect of the book in our posts; Playing to Win considers social class, race, gender, and other factors that I am choosing not to include in my own post, rather than risk losing all of you with a 4000 word missive. (My alternate universe post would have been about little boys being encouraged to participate in dance. But I feel rather strongly about that subject, and I just couldn’t do it justice by fitting it into today’s post.) So please forgive my inability to incorporate all relevant themes today- if you are interested in this subject, I encourage you to read the entire book!

Before I continue, let me explain something about this book: it has many, many layers. Playing to Win is an extremely comprehensive, well-researched, insight-laden look at competitive activities for children in America. There is simply no way that any of us can include every aspect of the book in our posts; Playing to Win considers social class, race, gender, and other factors that I am choosing not to include in my own post, rather than risk losing all of you with a 4000 word missive. (My alternate universe post would have been about little boys being encouraged to participate in dance. But I feel rather strongly about that subject, and I just couldn’t do it justice by fitting it into today’s post.) So please forgive my inability to incorporate all relevant themes today- if you are interested in this subject, I encourage you to read the entire book!

Last month I focused on my initial reaction to the first half of the book– specifically, the correlation between competitive activities and parents’ frenzy to prepare their children for college admissions. I shared Levey Friedman’s 5 tenets of Competitive Kid Capital– qualities that parents hope their children gain from participation in such activities– and expressed my feelings of disdain for pressuring children to succeed at such an early age. However, mixed in with my contempt for this early push to help our children “get ahead,” I also confessed my own anxiety that perhaps I am not doing enough to prepare my children for their future in an undeniably competitive culture.

How Do the Kids Feel?

But there is another layer to the book; in addition to what parents are hoping to accomplish by encouraging (insisting?) their children to compete, what about how the kids themselves feel? What do they get out of it? Certainly they are not continuing to play in the soccer league because their sights are set on Harvard? (Although, sadly, I’m quite certain that is at the forefront of some 8-9 year old children’s minds.)

So what motivates these kids to continue to compete? Levey Friedman, through extensive interviews with parents, determined that parental rewards are often part of the deal. Trophies only go so far to sate children’s sense of victory, and many parents often incorporate treats, gifts, and even cash as an extra incentive to ensure their kids’ best efforts. Levey Friedman states,

Once money is involved, kids start to become motivated by real scrip, as opposed to what was once a simple (fake) gold, shiny trophy.

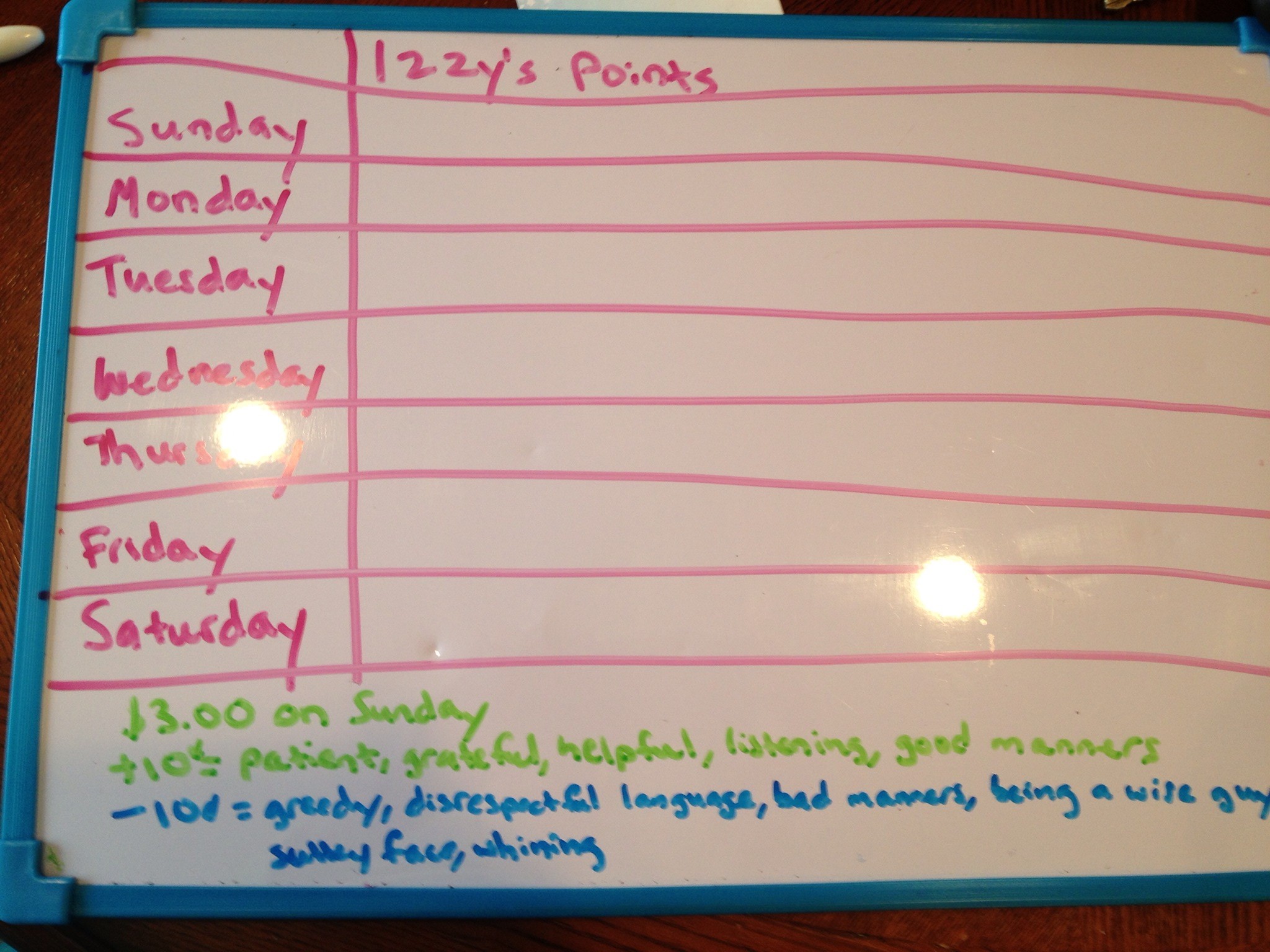

Perhaps it is hypocritical, but this sort of horrified me. I mean, isn’t it better for kids to try their hardest because of some intrinsic motivation and pleasure? I instantly realized this was a bit naive, not to mention, I have often lamented the fact that intrinsic motivation isn’t always realistic with kids. I too have created elaborate reward systems–offering money, toys, and treats– but that was always for good behavior and attitude, which somehow seems nobler than bribing your kids to play a better game of chess. But is it?

Our attempt, now discarded, to inspire optimal behavior in our oldest child.

Is participating in competitive activities fun for kids? I believe that each child has different interests, motivations, and thresholds for busy-ness. My oldest daughter, for example, highly prefers that the majority of her after-school and weekend time be unstructured. One father interviewed expressed concerns about his focus on providing a good future for his children, musing, “What if we are just taking something away from them?” He later commented that he often encourages his daughter to waste her time now, rather than waste it some other time in life. Isn’t this the time when kids should be carefree?

Competing Against Friends

One of my favorite parts of Playing to Win was the section that discussed friendship. Levey Friedman admitted that she hadn’t thought about this element until one of the girls she interviewed brought it up- to me, this aspect matters perhaps more than anything. When I was involved in high school music competition, the camaraderie was one of the highlights for me. Levey Friedman notes, “Being part of a team and developing friendships is one aspect of the competitive experience often discussed by children.” She indicates that in spite of the competitive spirit, teammates are proud of one another’s accomplishments and often develop bonds that extend past their practice and tournaments.

As a parent, this would bring me great pride and pleasure, but it is not always the case. One of the lines that shocked me the most was, “…it would worry some of the parents to know that their kids are using teamwork as a crutch to prevent individual excellence.” She mentions that close friendships can be a positive thing for kids, but may also undermine some of the skills that are important to their parents. The desire for children to view one another as friends rather than competitors may impact their efforts to be the best. My first thought was, “Really? Who the hell cares?” But clearly, that viewpoint is somewhat naive and reflects my own values.

I remember competing against my best friend in a vocal competition during my junior year of high school. The winner would win the state level and advance to a regional competition. I came in first place, and my best friend received the honorable mention. After the judges delivered their scores, we hugged each other and sobbed as only dramatic, deeply bonded high school girls can do. This moment was more important to me than winning. We both did our best. Neither one of us held back. But our friendship was simply more important.

Although some of the children interviewed in this book complained about not having time to relax, Levey Friedman indicates that they do enjoy participating in these activities: “Despite the tears, the pressures, and the judges, girls and boys do find participation in their competitive activities fun. They enjoy being with their friends, and it is fun to win, fun to be at events, fun to win trophies, and fun to participate in the activities themselves.” They learn to adapt to their busy schedules and lives. It is unclear what the long-term implications will be for kids who are involved in such intense competition. Will they become more successful than their uncompetitive peers? Will they be happier? Will they burn out?

In Conclusion

Levey Friedman concludes her book with a refreshing, balanced, “buffet” philosophy. She describes childhood as a buffet in which children should be free to sample many dishes and return for their favorites; she intends to approach her own child’s after-school activities based on this viewpoint, allowing him to sample many activities in order to find out his strengths and interests. She mentions that all parents are trying to do the right thing to ensure their children’s happiness and future. Even, I would add, to their own detriment. According to Levey Friedman, “While some parents bemoan the loss of family dinner time, others embrace the hectic schedule and see it as training their kids to balance various obligations later in life, developing Competitive Kid Capital that will lead to later success.” One of the most striking lines in the conclusion is,

Despite their unhappiness and ambivalence, parents continue to sign their children up for these activities.

Is it unrealistic for me to think that I am keeping my daughters’ happiness and best interest at heart by failing to subscribe to this culture? Or is this about my own discomfort with embracing the competitive lifestyle? When I think about the values these children gain– their Competitive Kid Capital traits– I can admit that they are desirable attributes and lessons for my daughters to gain. It is difficult to find fault with our children learning to bounce back from loss, perform under pressure, and develop confidence and perseverance. But I still can’t get on board with the idea of my 2nd grader competing.

These girls were certainly not fantastic performers at their recital- but they had a great time together.

I consider my own low threshold for feeling over-scheduled, running around, and squeezing too many things into one week. It makes me wonder if my own temperament is one of the reasons our family will likely refrain, barring some unforeseen God-given talent that is still lying dormant in one of our kids, from joining this world of competitive activities. As it is, shuttling around my two children, teaching classes, writing, socializing, and participating in one extremely un-competitive after-school activity is often more than I can handle.

Introducing Next Month’s Book!

On that note, I am so excited about our selection for next month- Maxed Out: American Moms on the Brink, by Katrina Alcorn.

From the Press Release: “Katrina Alcorn was a 37-year old mother of three with a loving husband and a dream job when one day, on the way to the store to buy diapers, she had a nervous breakdown. Her carefully built career came to a halt, and her journey through depression, anxiety, and insomnia– followed by medication, meditation, and therapy– began. Over time, as she began to ask herself how she was unable to meet the demands of having a career and a family, she realized she wasn’t the only one. “

Whether or not you have experienced an actual nervous breakdown, I am betting there are aspects of that paragraph that many of us can relate to. As a mother of two who works part-time every morning of the week, teaches several afternoon classes, and attempts to frantically cram writing and blogging into the remaining spaces, I get it. I experience my own version of maxed out nearly daily. I am so eager to read this book; I look forward to reading Alcorn’s story and hearing her perspective on why American women seem to be falling into this trap of “doing it all.” Are we setting ourselves up for failure? Is it our own faults? What can we do differently to protect our own sanity as well as preserve the integrity of our ambitions?

I am hoping that reading Maxed Out will answer some of these questions. If you are anything like me, frazzled at times, searching desperately for balance, and struggling to “do it all,” I bet this book will speak to you as well. Please consider reading along with us- we look forward to hearing your thoughts! Join us again for our discussion on Monday, December 2nd!

You can read the other Brilliant Book Club posts here:

Urban Moo Cow: Playing to Win But Thinking For Yourself

School of Smock: From Strong Girls to Maxed Out Women

Left Brain Buddha: Soccer Mom, Aggressive Daughter. Dance Mom, Effeminate Son?

Kevin and I were just having this conversation last night, because the girls did dance for the last two years and this year we tried soccer. I know they have also expressed interest in gymnastics, but both of us really don’t want them doing more then one activity like this at a time. We just feel at their age it may be too much, plus I will be honest doing one organized activity a weekend is more then enough for us, too. So, yes can relate and thank you for sharing this book here with us today,

I totally agree with you- at this age, less is definitely more! 🙂

Your next book sounds AMAZING! I have really enjoyed this book discussion as well. I definitely like the “buffet” approach as well…seems the most balanced.-Ashley

I think we will all love Maxed Out! 🙂

It’s funny, I didn’t take away the “balanced/buffet” approach from her conclusion. I felt that she was “all in” in terms of subscribing to the philosophy. She concluded that it is here to stay, but I didn’t sense as much reluctance as I feel.

Anyway, I also found the chapter about the kids really interesting. I remember reading that the kids *knew* there was some ulterior motive for all these events. That it wasn’t really all about fun, even if fun is what they mostly took away from it.

It’s true I’m not reluctant about it, but I think that’s because I think/hope our family knows it matters but it doesn’t MATTER. I do think (per your post which I will get to) that it is the way the world works, so on some level we have to get on board as parents.

And, yes, kids took away fun but also the ulterior motive. I basically think about the friendships has a coping mechanism for dealing with the stress of competition.

It’s possible I took away what I wanted from the ending. 🙂 Nothing like adjusting your interpretation to validate your own choices!

I relate to your feelings and your approach a tone. With four kids and with our refusal to do activities on Shabbat (Friday nights and Saturdays) we know that we cannot keep up. So we don’t try very hard. I’ve found a decent house league where my oldest can play soccer. That 6-week session just ended. Now that it’s cold there isn’t another. That experience will have to do for now. My girls take a gymnastics class together. It’s a class–not a team. They’re still young though. It’s not that I don’t value what comes from teams and competition. But neither my husband nor I value it above everything else. We aren’t willing to do what it takes to really participate in the level that it would require for our kids to get fully involved. I try to think about what they’re getting (time to play, family time, less hectic life, less stressed out parents) than what we’re losing.

Love the approach of what we get as opposed to what might be lost! I should apply that to more things in my life in general…

I agree- that last line is perfect. Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Nina- I really appreciate your wise, balanced perspective!

As I wrote already you saying the book is multi-layered, etc. is one of best things ever said about book! And I love that it made you pause and think about different aspects of your life. It does look like your daughter is having fun at dance– especially with her friends.

It definitely did make me think, Hilary, and I’m glad you are pleased with my assessment. I thought it was important for readers to understand that the book was not as myopic as one blog post is able to portray!

I confess I didn’t read that final chapter (bad teacher!) so this was interesting ~ with gymnastics, and only 5 varsity spots per event, I do remember feeling resentful about meet lineups (especially when my little sister was placed ahead of me), and I coached our high school’s varsity team for several years, and doing lineups and also considering the girls’ relationships was really stressful. The other coaches and I joked that we also needed to be psychologists to coach!

I think we’re all in agreement that if our kids are enjoying it, and we have the time and resources for it, and our kids still can sleep and have time for free play, a little healthy activity involvement, and even competition, will be okay. I think our attitudes play such a role in how our children perceive these events, too.

Ha! There would definitely be a benefit to having a psychology background when coaching, eh? Our attitudes are hugely central, I think.

Really wonderfully written, Stephanie. Perhaps I, too, am naive but I choose my son’s happiness every time. In fact, it’s completely horrifying to me that parents continue to push so hard “despite their unhappiness and ambivalence.” That’s just sad. We played sports as kids and for me, the team and the camaraderie around it was The Best Part. Loved your Izzy Chart. Most especially the -10cents for greedy, disrespectful, etc. Awesome. Also, I should say that for a couple of years, my dad paid my brothers and I for report card A’s. The money wasn’t motivating. He discontinued at some point because he’d decided that it was wrong. I’d forgotten all about that.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts- clearly, you and I are on the same page! 🙂

This was a fascinating read and I would have loved to have read your article about boys being encouraged to take ballet.

Much like you, Stephanie, I found myself really taken aback by this sentence “She mentions that close friendships can be a positive thing for kids, but may also undermine some of the skills that are important to their parents.” It almost sounds like counter-intuitive parental behaviour or approach that’s demonstrated by the parents who rationalize this way. It’s hard to fathom and I almost wonder whether these parents get it and are making a conscious choice of ‘winning’ vs. friendship or whether they’re just so caught up in the game that they can’t see straight?

I loved the example you’ve used of your own high school vocal contest I think that was a wonderful illustration of kids’ and teenagers’ natural inclination.

At the risk of sounding creepy or cheesy, you have always reminded me of my high school best friend that I mentioned in this post. You have the same lovely energy. xo

You can never out-creep me, my friend. 🙂 And, no, not creepy at all. Very heartwarming, actually 🙂

Both my husband and I played sports all the way up until I destroyed my back and he got the taste for beer and lazy…kidding…he still plays. We both got so much out of taking part in sports. It was only natural that we sign up our son for things that he had interest in.

I want him to be able to enjoy it and learn from it. Sports go far beyond the stage, field, rink etc. It introduces teamwork and to put your all into everything even when you’re “losing”.

I think the balance in all of this is that we pay attention to what they want. we cannot force them into something that they don’t want to take part in.

As a teacher, I have definitely seen that some kids enjoy competition and some don’t, so I think it is impossible to say whether competition is good or bad. Really, it depends on the kid. I think the hard part is staying in tune with the child and figuring out what his or her motivations are.